Practicalities: Open Wed-Sun 10 to 5. GPS 55.784956,37.616669. Take the metro to Dostoevskaya then go about 100m North on Ul Sovetskaya Armee and look for the ICBM.

|

|

|

Abkhazia Afghanistan Albania Alexander Antarctica Armenia Australia Azerbaijan Belarus Bhutan Bolivia Brazil Brezhnev Burundi Canada Chile China Costa Rica Cuba Cyprus DR Congo Ecuador Egypt Eritrea Ethiopia fire France French Guiana Georgia Germany Greece Greenland Guyana ICBM Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Italy Japan Kazakhstan Kenya Kosovo Kyrgyzstan Latvia Lava Lebanon Lenin Madagascar Martinique Mauritius Moldova Mosaics Myanmar Nagorno-Karabakh NASA Nicaragua North Korea Norway Pakistan Palau Paraguay Philippines PNG Poland Russia Rwanda Saudi Arabia South Ossetia South Sudan Sri Lanka Stalin Stans Sudan Suriname Syria Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Tibet Transdniester Trinidad Turkey Turkmenistan Ukraine USA USSR Uzbekistan Venezuela Vietnam Xinjiang Yap Yemen

Practicalities: Open Wed-Sun 10 to 5. GPS 55.784956,37.616669. Take the metro to Dostoevskaya then go about 100m North on Ul Sovetskaya Armee and look for the ICBM.

|

|

|

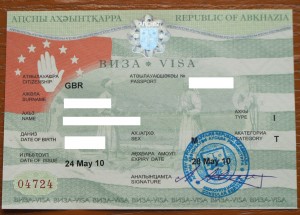

Before I arrived in Georgia, I had applied to the Abkhazian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sukhumi for a visa to visit Abkhazia. After a little toing-and-froing I was assured that my visa would be waiting in Sukhumi and my name would be on the “approved list” at the incoming border checkpoint.

Before I arrived in Georgia, I had applied to the Abkhazian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sukhumi for a visa to visit Abkhazia. After a little toing-and-froing I was assured that my visa would be waiting in Sukhumi and my name would be on the “approved list” at the incoming border checkpoint.

I took a taxi from  Zugdidi to the Abkhazia border, arriving at around 8:50am. On the Georgian side, there was much careful writing down of my particulars (name, nationality, passport number, date of birth, place of birth) and a couple of phone calls “to officer” to get the OK. Everyone was quite friendly and it took about ten minutes. I was warned to beware of thieves on the Abkhazian side.

Zugdidi to the Abkhazia border, arriving at around 8:50am. On the Georgian side, there was much careful writing down of my particulars (name, nationality, passport number, date of birth, place of birth) and a couple of phone calls “to officer” to get the OK. Everyone was quite friendly and it took about ten minutes. I was warned to beware of thieves on the Abkhazian side.

On the way towards the border, still on the Georgian administered side, there is a strange sculpture of a giant revolver pointing towards Abkhazia, with the barrel tied off. Interpretation is left to the viewer.

There was then a long trudge, perhaps 1.5 km, down a road and over a bridge to the Abkhazia checkpoint. Naturally the route was in dismal repair, with giant puddles. There was moderate rain. Sigh.

There was then a long trudge, perhaps 1.5 km, down a road and over a bridge to the Abkhazia checkpoint. Naturally the route was in dismal repair, with giant puddles. There was moderate rain. Sigh.

On the Abkhazia side, with no thieves anywhere in sight, a cheerful young passport officer with no English confirmed that my name (with maybe a dozen others) was on a handwritten list on his desk. I was then waved through. It took less than 5 minutes.

I was out and in the minibus for Gali around 9:30. But (perhaps due to the rain) it was a slow day and it wasn’t until around 10:30 that we had a full bus and left for Gali. We got to Gali around 11:00. After a little dithering, and the persistent assertion that there would be no bus for several hours, I agreed to pay for a taxi to Sukhumi. We zoomed off, then a few minutes later abruptly U-turned and zoomed back. It turned out the driver needed to go home to collect his license (I guess he normally doesn’t need it?).

The area of Abkhazia around Gali is very decrepit. Although many buildings seemed OK, I also saw several ruined buildings, probably from the 1993 war. Much of the farmland seemed untended and growing wild. The road was very bad, and we were continually veering from side to side to avoid potholes and puddles. (The rain was now heavy.) After we reached the coast (Ochamchire) the road and countryside improved dramatically. By Sukhumi the road was fine.

The driver dropped me off at the Hotel Ritsa. I dutifully hunted down the correct bank (“Сбербанк”, hidden in the Customs Yard) to pay my 641 Russian Rubles visa fee, got my payment voucher and headed off to the MFA building. While searching for the Consular office, I accidentally wander into a small theater area and hurriedly backed out again. But after some searching, I found that this really was the room being used by the Consular Section and the people on the stage with desks and PCs were the consular staff, not actors holding a rehearsal. Eight minutes later, I was duly issued my Abkhazia visa. Hurrah!!!

The driver dropped me off at the Hotel Ritsa. I dutifully hunted down the correct bank (“Сбербанк”, hidden in the Customs Yard) to pay my 641 Russian Rubles visa fee, got my payment voucher and headed off to the MFA building. While searching for the Consular office, I accidentally wander into a small theater area and hurriedly backed out again. But after some searching, I found that this really was the room being used by the Consular Section and the people on the stage with desks and PCs were the consular staff, not actors holding a rehearsal. Eight minutes later, I was duly issued my Abkhazia visa. Hurrah!!!

The Hotel Ritsa is trying hard to be a first rate hotel. It has been recently renovated and my room has first rate fittings, with rather erratic installation. For example, the elegant chrome toilet roll holder fell off in my hand and all the faucets were loose. But it was actually all fine and comfortable, just slightly eccentric.

Later, I ambled around central Sukhumi in occasional drizzle. The city is a little drab, but the central areas have now (mostly) been repaired. I passed the burned out, but structurally intact, Presidential Palace. (A victim of the 1993 war.) There is a large empty plinth in front, which I suspect once held Lenin.

Sukhumi in occasional drizzle. The city is a little drab, but the central areas have now (mostly) been repaired. I passed the burned out, but structurally intact, Presidential Palace. (A victim of the 1993 war.) There is a large empty plinth in front, which I suspect once held Lenin.

The following morning, the rain stopped and the day cleared up nicely: Sukhumi is much more fun in the sun! It is at about the same latitude as Nice after all.

The Abkhazians clearly love their palm trees and their beautiful pebbly beach. I dutifully wandered through the pleasant Botanical Gardens and admired their many semi-tropical plants and also their fine water lilies.

The Abkhazians clearly love their palm trees and their beautiful pebbly beach. I dutifully wandered through the pleasant Botanical Gardens and admired their many semi-tropical plants and also their fine water lilies.

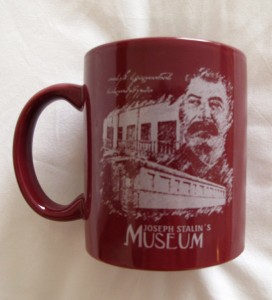

Despite the 2008 war, neither Gori nor its famous Stalin Museum seem to have changed much since my previous visit in 2007. The tall statue of Stalin still dominates the town square. The Stalin Museum still provides a positive narrative of Stalin’s life with a focus on the great Soviet WWII victory, and no mention of any awkward topics. The only change I noticed was the addition of a small gift shop, where the faithful can buy commemorative tee-shirts and mugs.

Despite the 2008 war, neither Gori nor its famous Stalin Museum seem to have changed much since my previous visit in 2007. The tall statue of Stalin still dominates the town square. The Stalin Museum still provides a positive narrative of Stalin’s life with a focus on the great Soviet WWII victory, and no mention of any awkward topics. The only change I noticed was the addition of a small gift shop, where the faithful can buy commemorative tee-shirts and mugs.

I know that Gori suffered some bomb damage in the 2008 war, as well as being briefly occupied by Russian troops. However there is no longer any visible damage in the central parts of town. In general, things actually seemed slightly more prosperous than I remembered from 2007.

[Update: The Gori Stalin statue was removed on 25th June 2010.]

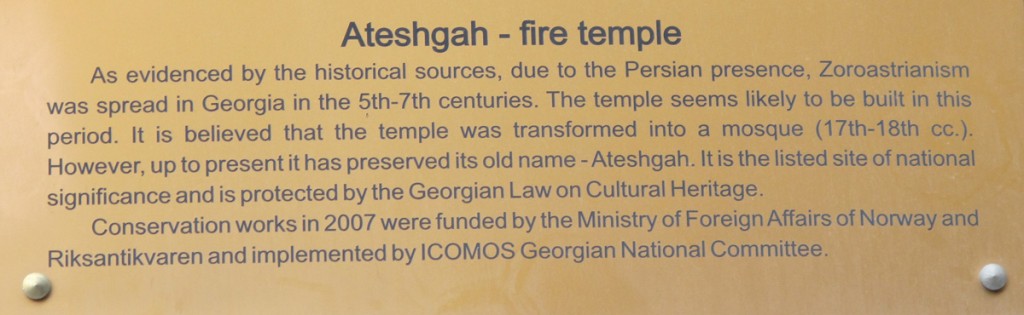

The Tbilisi Ateshgah (aka Atashgah or Fire Temple) was under restoration when I visited it in 2007. That work is now complete and, mercifully, the restorers have been gentle. The old brickwork has been cleaned, and in a few places discreetly repaired, but has largely been left “as is”, without any gross tampering. A perspex roof has been added to protect the site from the elements.

The Tbilisi Ateshgah (aka Atashgah or Fire Temple) was under restoration when I visited it in 2007. That work is now complete and, mercifully, the restorers have been gentle. The old brickwork has been cleaned, and in a few places discreetly repaired, but has largely been left “as is”, without any gross tampering. A perspex roof has been added to protect the site from the elements.

Authentic Zoroastrian fire temples are extremely rare, especially outside Iran. (The Atashgah at Baku is an 18th century Parsi construction.) According to the sign outside the Tbilisi temple, it is believed that it was built between the 5th and 7th centuries, and later spend a while as a mosque, while retaining its old name as “Ateshgah”. This seems reasonably plausible as Tbilisi was under Persian occupation and influence for a while. Zoroastrianism (like Christianity) was loosely tolerated under Islam, so the Ateshgah might easily have survived in active use for several centuries after the 7th c. Arab invasion.

The Ateshgah exterior is a largely featureless brick cuboid, perhaps 20 feet on a side. There are steps leading up to a pair of stout wooden doors just to the left of the Ateshgah. These open into what at first looks like a private family courtyard, but if you turn right actually leads into the Ateshgah interior. There is a new wooden floor, but they have left parts of the original floor exposed. There are no windows, but instead there are blank arches on each face.

The Ateshgah exterior is a largely featureless brick cuboid, perhaps 20 feet on a side. There are steps leading up to a pair of stout wooden doors just to the left of the Ateshgah. These open into what at first looks like a private family courtyard, but if you turn right actually leads into the Ateshgah interior. There is a new wooden floor, but they have left parts of the original floor exposed. There are no windows, but instead there are blank arches on each face.

Back in the day, a sacred flame would have burned here and there would likely have been a matching pool of clean water nearby. A small hollow is visible in one corner, but it isn’t clear what purpose (if any) that served.

The Ateshgah is at GPS = 41.68885,44.80559 around 100 meters East of the Betlemi Church, on the Old Town slopes NE of the Mother Georgia statue. You can find it by first heading South from Freedom Square, then heading east along Asatiani Kucha, then take the first right (South) onto a short road that leads up to the Betlemi stairs, then take the 135 steps up to the Upper Betlemi Church, and then head East, past the Betlemi Bell Tower. Look for the ancient brick building with the protective curved perspex roof!

The Stalin Museum in Batumi is much more modest than the imposing Gori Stalin Museum. It comprises three mid-sized rooms, in a former worker’s hostel which housed the young Stalin when he was organizing workers in Batumi. However, the Batumi museum provides a much more personal and enthusiastic touch than in Gori. Your 3 Lari admittance fee includes a guided tour (in slightly halting but workable English) from the Museum’s curator. It quickly becomes clear he has true enthusiasm for his work and he believes Stalin was, on the whole, a positive force. He uses the familiar arguments: without the crash industrialization program of the 1930s the USSR (and the West) would have lost WWII and, without Stalin, the crash industrialization program would never have happened.

Stalin ‘s stay in Batumi was reasonably brief. He was arrested and imprisoned after organizing a workers protest where a number of workers died in a confrontation with the authorities. (See Simon Sebag Montefiore’s “Young Stalin” for details.) The museum includes the room where Stalin stayed and supposedly the actual bed he slept on. Other than that, it includes a modest collection of idealized Stalin paintings and sculptures, and reproductions of various stock photographs of the young revolutionary, including his classic police mugshot.

Since I seemed interested and polite, the curator was kind enough to take my picture with a flag of the Soviet Republic of Georgia, beside an idealized statue of the young Stalin.

If you are in Batumi, it is definitely worth visiting, if for nothing else, as a glimpse into an entire alternative world view.

The stunningly green Siwa oasis is in the outer Sahara, in Western Egypt. I got there after about 470 miles and ten hours by bus from Cairo, with a change of buses at Marsa Matruh on the Mediterranean coast. The first sign of Siwa was hills off in the distance and then an abrupt terrain transition from Saharan sand to tall wild grass. Then we entered the oasis proper, with its many acres of lush green palm trees.

The stunningly green Siwa oasis is in the outer Sahara, in Western Egypt. I got there after about 470 miles and ten hours by bus from Cairo, with a change of buses at Marsa Matruh on the Mediterranean coast. The first sign of Siwa was hills off in the distance and then an abrupt terrain transition from Saharan sand to tall wild grass. Then we entered the oasis proper, with its many acres of lush green palm trees.

The oasis has a population of around 10,000, with much local agriculture and a good scattering of tourists. At the bus stop I was ambushed by some local kids, who carefully declined to give me directions to my hotel, but instead sold me a ride there on their fine donkey cart, for a whole 5 Egyptian Pounds (about a dollar).

Now palm trees and donkey carts are all very charming, but Siwa’s main claim to fame is that it was the site of the great Oracle of Amun. Among many other visitors, Big Alex came by here in 331 BC. We don’t know what question he asked, but we know the gist of the wise answer he received: “Alexander is the son of Amun and destined for Great Things!”

Now palm trees and donkey carts are all very charming, but Siwa’s main claim to fame is that it was the site of the great Oracle of Amun. Among many other visitors, Big Alex came by here in 331 BC. We don’t know what question he asked, but we know the gist of the wise answer he received: “Alexander is the son of Amun and destined for Great Things!”

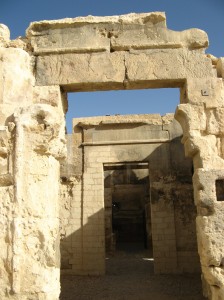

The Temple of the Oracle is about 2km East of the modern town area. It is easy to spot, as it is inside a ruined mudbrick town on a prominent hilltop. The Temple is fairly modest, and has suffered from some aggressive modern reinforcement of the ancient structure. But yes, it is the original structure, built in the 6th c. BC and visited by Alexander himself. The inner sanctuary is blocked off by a modern iron gate, but that was open when I was there, so I could stroll into the heart of the ancient Oracle.

The Temple of the Oracle is about 2km East of the modern town area. It is easy to spot, as it is inside a ruined mudbrick town on a prominent hilltop. The Temple is fairly modest, and has suffered from some aggressive modern reinforcement of the ancient structure. But yes, it is the original structure, built in the 6th c. BC and visited by Alexander himself. The inner sanctuary is blocked off by a modern iron gate, but that was open when I was there, so I could stroll into the heart of the ancient Oracle.

I had arrived early, so I had the site to myself. After traveling so far, how could I resist asking the Oracle for guidance? A long pause and then the exasperated braying of donkeys in the distance. A fine and fitting answer.

From the hilltop there is a fine view over the oasis, with its many square miles of green palms, and its two large (salty) lakes to East and West.

The ruined Temple of Umm Ubayd is about 500 meters SSE of the Oracle. (Note that the map in Lonely Planet Egypt 2008 seems to have mixed up the locations for the two temples and is quite misleading on this point). The humble road between the two temples is decorated by giant green lamp posts. Follow the lamp posts through the various forks and you’re on the right route. Unfortunately there isn’t much to see at Umm Ubayad: a lot of large collapsed blocks and a restored wall with a few faded ancient Egyptian inscriptions.

The ruined Temple of Umm Ubayd is about 500 meters SSE of the Oracle. (Note that the map in Lonely Planet Egypt 2008 seems to have mixed up the locations for the two temples and is quite misleading on this point). The humble road between the two temples is decorated by giant green lamp posts. Follow the lamp posts through the various forks and you’re on the right route. Unfortunately there isn’t much to see at Umm Ubayad: a lot of large collapsed blocks and a restored wall with a few faded ancient Egyptian inscriptions.

If you follow the green lamp posts about another 700 meters SE, you’ll find a large modern bathing pool, allegedly fed by the ancient “Cleopatra’s Spring”. A little further on, there is an older, but still modern, circular deep pool, with a little water bubbling up, which also claims the “Cleopatra’s Spring” title.