Most relics of Stalin were swept from public view in the USSR in the years after Khruschev’s 1956 denunciation. But not in Gori, Georgia.

Most relics of Stalin were swept from public view in the USSR in the years after Khruschev’s 1956 denunciation. But not in Gori, Georgia.

This small provincial town is Stalin’s birthplace. I suspect that Stalin is pretty much the only interesting thing ever to have happened here, so, despite everything, he is still commemorated as the local boy who went on to Great Things. His statue, birthplace and museum are all still preserved, if no longer explicitly venerated.

After my 70 minute marshrutka ride from Tbilisi, I was dropped off in the Gori’s main town square. This is dominated by a tall and imposing statue of a mustached figure in a military greatcoat. There is no inscription. Back in the day, none was needed.

Heading North from the square, I spotted what initially appeared like a smallish Greek temple. But no. This is the site of the modest house where Stalin was born and raised. That modest two room brick building has been lovingly preserved and, to protect it from the elements, a temple like outer structure has been erected over it. On the North side is a second, smaller statue of Stalin, this time in a softer, more relaxed pose.

Heading North from the square, I spotted what initially appeared like a smallish Greek temple. But no. This is the site of the modest house where Stalin was born and raised. That modest two room brick building has been lovingly preserved and, to protect it from the elements, a temple like outer structure has been erected over it. On the North side is a second, smaller statue of Stalin, this time in a softer, more relaxed pose.

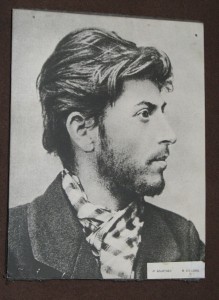

The Stalin Museum itself lies just to the North of the preserved house. The museum has a wide array of Stalin paraphernalia, including reproductions of early photographs of the young “Soso”, a copy of Stalin’s first police mugshot, his first desk in the Kremlin, historical exhibits from WWII and Yalta, an array of his favorite pipes, gifts received from foreign governments, and finally his bronze death mask.

My favorite piece is definitely the Tsarist police mugshot. It casts such a different light on Stalin: as the wild young revolutionary, rather than the smug middle-aged dictator.

My favorite piece is definitely the Tsarist police mugshot. It casts such a different light on Stalin: as the wild young revolutionary, rather than the smug middle-aged dictator.

A guide took me inside Stalin’s armored railway carriage and we tiptoed nervously past the compartments where the great man had slept and worked.

The Museum presents its artifacts without commentary: neither praising nor denouncing. But of course the choice of exhibits is itself significant: we are shown Nazi banners being flung at Stalin’s feet during the great Soviet WWII victory parade, but we are not shown any hints of the Gulag, let alone of the Great Terror. In an unintentional piece of symbolism, the elegant clock outside the museum is stopped: permanently frozen at the High Noon of the Soviet Empire.

As background reading on Stalin’s Georgian youth, I’d strongly recommend Simon Sebag Montefiore’s “Young Stalin” which paints a very vivid picture of Stalin’s time in Georgia, showing his different roles as a seminary student, a star choirboy, a proud Georgian poet, a rabble-rousing Marxist, a ruthless underground Bolshevik leader, and an organizer of daring bank robberies, supplying badly needed cash to Lenin’s headquarters.