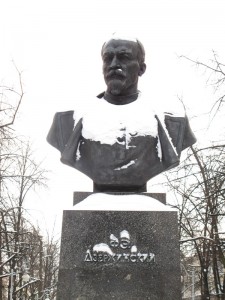

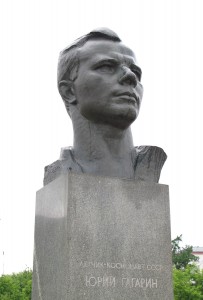

The Brest Fortress complex commemorates the heroic defence of the Soviet garrison against the German invasion of June 1941.

I also ambled through the Fortress Museum, which has some displays of the 19th c. fortress, and even a very short display on the 1939 Polish defence, but which is naturally focused on the 1941 defence, with many photos of the defenders.

Commentary: In 1941 the Soviet Union desperately needed some heroic myths, and the “Defence of the Brest Fortress” fit the bill. A small group of heroic defenders, stemming the flow of the German invasion. It’s a good story and I don’t doubt the defenders were truly heroic. However the German advance seems to have been focused on deep penetration and encirclement, which implies bypassing fortresses and fixed defence points and leaving those to be mopped up later by secondary forces. So the leisurely siege is unlikely to have impacted the main invasion.

The following day: At the Brest station, I met three unhappy travelers, two Americans and a Dane. They had been taking the train from St Petersburg to Warsaw and hadn’t realized that their train took a non-obvious detour through Belarus. There are no immigration checks at the Russian-Belarus border, so they had been able to enter Belarus, but then when they were exiting at Brest they were caught by Belarus immigration. Traveling in Belarus without a visa: not a good situation! They were removed from the train and delayed for two days in Brest. They were finally allowed to exit after signing “a big stack of forms” and paying moderate fines (about $200 for the American couple) for having entered Belarus illegally.

![Brest Fortress Entrance [Brest Fortress Entrance]](/photos/GoDaddy/Brest/minis/Entrance.jpg)

![Brest Honour Guard [Brest Honour Guard]](/photos/GoDaddy/Brest/minis/HonourGuard.jpg)

!["Thirst" ["Thirst"]](/photos/GoDaddy/Brest/minis/Thirst.jpg)

![Obelisk [Obelisk]](/photos/GoDaddy/Brest/minis/Obelisk.jpg)